- Persistent cat gets the bag

- Six dozen of one, half horse a piece

- Buckle down the hatchet

- Cut bait or don’t

- Get off of the pot

- Double down dare ‘em

Author: Clinton Forry

Content Strategist and writer. Fancier of vinyl LP records. Tall. Bit of a dandy. Also: whiskey.

- Sally Mae

- Annie Mae

- Dazie Mae

- Miss Rosie Mae

- Miss Sadie Mae

- Mai Lee (alternate spelling of Mae)

Q: What is this “WD45” I see you going on about?

A: My grandfather owned Allis Chalmers farm tractors and equipment. So does my father. Growing up on the farm, I learned to drive a tractor [an Allis-Chalmers WD-45 model, among others] long before I learned how to drive a car.

I started using “WD45” online in the late 90s, on bulletin boards as a short username with some personal history behind it. At that point, it became relatively clear that I would not be driving tractors for a living. This moniker serves as a persistent reminder of my family’s rural and agrarian legacy and the hard work that built it.

As a kid [and as an adult] I have been an enthusiast of this tractor company and its history of innovation. I actually have a collection of Allis-Chalmers marketing and promotional films from the 1940s, 50s, and 60s. They have taught me a lot:

- The odd diction of mid-20th century industrial film voice-overs

- Clear messaging that keeps in mind the audience’s station

- Industrial design and innovation shines in the service of real needs

If you see someone online with the username WD45, it’s probably me. I’ll even sign up for a new service just to claim that username.

Four characters, easy to remember. It just stuck. To this day, it still sounds funny when people say it out loud. Especially when they are referring to me, and not a tractor…

An example of an Allis-Chalmers promotional film:

Old-fashioned readability scores and indices don’t account for some of the most critical elements of online content presentation. Avoid using them as the only measure of the true readability of online content.

The story of a story

“Go Dogs. Go!” I love this book. Well, a version of this book. (The small one.)

Several popular children’s books from publisher Random House are available in two physical formats: the standard hardcover book and the board book. Each format has its pros and cons.

- Hardcover book. More, thinner pages for more content. But, thinner pages tear easier.

- Board book. Fewer, thicker pages means less content. Super durable.

The more / less content situation wouldn’t be an issue if you were writing a book from scratch.

Instead, publishers are most likely taking their more popular, large-format titles through an editing and re-versioning process. In the end, they can introduce a more durable version to another audience: page-chewing babies.

Getting to the point

This content editing process HAS to be complicated, from an editorial point-of-view. Imagine the task of conveying the familiar storyline in one-sixth the number of words.

In the case of “Go, Dog. Go!”, the longer, hardcover version was trimmed from 528 words to only 70 words in the shorter, board book version. Each one of those 70 words matters, believe me. (I’ve read it hundreds of times.)

Sure, there are fewer words. But, fewer words doesn’t always make a message or story clearer and easier to read.

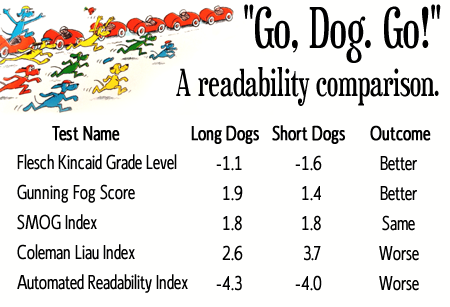

Testing the readability of “Go, Dog. Go!”

Readability tests are equations using syllables, word counts, sentence counts, and familiar-word lists. Most often, they produce a number that corresponds with a grade level.

From a readability metric standpoint, you might think that such a dramatic reduction in content (the 528 versus 70 words) would make the story easier to digest. Based on five of the major readability tests, results were mixed.

Two tests showed improvements in readability in the shorter version, one saw no change, and two others came back with less favorable scores:

While the goal of the publisher, editor, and author is fitting the same, beloved storyline into fewer pages, another, more-interesting thing starts to happen: a brutal distillation. Only the essential remains.

The shorter version of “Go, Dog. Go!” sheds some of the more superfluous elements of the story. Gone are the hat-disapproving dog, unrelated sub-plots, and unnecessary filler. What we are left with is pure magic. Seriously, you need to read this short version. I still love reading it.

Why we test content readability

Some of us might test content JUST FOR FUN. Others are tasked with the duty of measuring how consumable the content is by some score or index. The duty of measuring readabilty does not end there. We want to:

- Determine if current content meets existing standards

- Establish a baseline readability score

- Set goals and standards for future content production

- Measure edited, re-vamped, and re-organized versions of the same content

How we’ve tested content readability in the past

The major readability tests were constructed in the 1940s to deal with printed texts. These equation-based systems improved the texts of the day: newspapers, books, etc. Familiar-word lists were refined, and other adjustments were made. Things were set for some time.

Research completed in the following decades took into account one of the foundational concepts for clear and concise online writing: structure. However, it proved impossible to fold structure-based variables into a traditional readability equation. Text needs are much more complex than could have ever been anticipated.

Today, a quick search online will produce several sites that offer options to measure content via cut-and-paste or by entering a page URL. Simple, quick, and easy. Right? NOT SO FAST.

This has an impact on online content

As we approach online content itself from a messaging and editorial standpoint, we encounter similar issues as seen in the children’s book example. Adjusting text content can have a positive or negative impact, depending on the test. The worst-case scenario has people adjusting text to game the tests into delivering favorable scores.

No current readability test accounts for the hallmarks of easily-consumed online content:

- Concise sentences free of filler words

- Bullets

- Subheads

- Emphasis (bold, H1, H2, etc.)

- Shorter, easily-read paragraphs

Add a few more variables into the equation by considering responsive design implications, device capabilities, and context, and soon the notion of an agreed-upon readability score is RIGHT OUT.

We are creating content destined for literally thousands of different environments. Even if we had a measure that took into account how that content was displayed now, it would by out of date in a week.

Don’t measure readability only with a number

Content strategists are often asked how we might measure the effectiveness of our efforts. Sometimes we can point to cost savings, favorable return on key performance indicators, or other data-based measures.

Other times, our value is best presented in refinements to the overall user experience. Which can be tough to measure with a series of numbers.

It’s hard to resist. You might be begging for an easy, scalable, plug-and-play solution for your online content readability measurement needs. Instead, you might wish to make a checklist of sorts, from a messaging point-of-view:

- Does this page/element stick to a single message overall?

- Does the content avoid jargon and language inappropriate to the audience ?

- Are the ideas presented in a clear, logical fashion from a user perspective?

- Does the page have a clear objective (and call-to-action, if appropriate)?

- Can users scan and quickly understand what they will get from the page?

Readability scores are not completely without merit. I still use them for passages and paragraphs, when appropriate. But they simply cannot be used for measuring an entire page’s readability.

In the meantime, go find the board book version of “Go, Dog. Go!” at your library. (I didn’t even let any story spoilers slip. The ending is AWESOME.)

Content devices, platforms, and delivery are becoming more complex. Our approach to these changes must retain a strong editorial approach in addition to advances in technology. OR ELSE.

A recent, delightful A List Apart article by the super-smart Sara Wachter-Boettcher, “Future-Ready Content,” brought back some memories for me. A few days later, Brad Frost’s article there, “For a Future Friendly Web,” did the same.

I remember hearing about something exciting back in 2009 or so. It was clear, simple, and full of hope. It had the answers. A silver bullet.

The concept was simple: Create Once, Publish Everywhere. It even had a smart acronym: COPE. Daniel Jacobson at NPR detailed the concept in a blog post.

We needed a COPE coping mechanism

Since 1996, I had been working in an industry that needed the help: public radio. TONS of content (old, new, and upcoming), new platforms, new audiences, and more.

It quickly became apparent that the COPE silver bullet had a bit of tarnish on it, from a marketing and distribution perspective.

COPE works best when there is a single content type, maybe two. Limited content types usually mean a corresponding limited number of end uses. Even then, in my public radio sphere, issues popped up:

- There was one format for broadcast by radio stations and one for sharing online

- Critical metadata was often incomplete

- A less-than-reader-friendly transcript sometimes accompanied the audio asset

- Hosting concerns about ancillary images or video

- Content lacked proper context for distribution outside of its native environ

Technical issues worried me in 2009. (They still do. Always will.) But, editorial issues cause me worry now.

Content, publishers become more sophisticated

COPE represents an important step in any content equation. Content is best when device-neutral. Structured content is here to stay, and rightfully so. (I even wrote about the concept “atomic content” on this blog in 2009.)

In a very basic sense, COPE gets things in order, preps the content for prime time. But it is incomplete.

We can’t forget about the life of content that starts after the publish process is complete. (I’m looking at you, Facebook, Twitter, and even Pinterest.)

As organizations create more future-ready content, they’ll need to make sure the folks with their fingers on the publish buttons know what they are dealing with. As the content becomes more sophisticated, flexible, and responsive, so too must those that plan, create, and deliver it.

This is the part where I hold up a big caution sign

I’ve had experience in other organizations with varying content workflows. Sometimes we are lucky to be in control up the content production river and down. Like on this blog, for example. (If there is a workflow issue, I’ll need to go stand in front of a mirror and work it out.)

Other operations are larger than content-ment.com. WAY LARGER. As content-producing operations scale up, things become more complex. WAY COMPLEX. Some difficulties:

- We content types might not be involved as much. In larger organizations, content experts may have limited opportunity to guide the content strategy process at each step: plan, create, distribute, and govern.

- Roles become much more specialized and decentralized. Some staff members may create concepts, others produce the content. And others yet may publish and distribute.

- People with different goals will be in charge of parts of the content lifecycle. Campaigns and concepts are often generated in different rooms than those close to the code and pixels.

- Departments have different levels of content literacy. Naturally, experience and approaches with content will vary. Some folks will have old media mastered. Others will be digital natives.

Marketers feeding ever-hungry channel-mouths would be DELIGHTED to see content formatted in a way that allows (and encourages, at least a bit) publishing everywhere, every time. That might lead to content ending up in places where it shouldn’t.

COPE makes the assumption that content (once produced, properly marked up, and made available via CMS or API) is suitable for any use. The everywhere in create once, publish everywhere is a marketing catastrophe waiting to happen.

Time to call the COPS

This is why I’ve wished that the acronym wasn’t COPE.

I’ve my own acronym. Rather than COPE, I want to call the COPS: Create Once, Publish SELECTIVELY. (No relation to the television show of the same name, however.)

It’s a bit more labor intensive, but the extra effort will make these endeavors more focused and effective.

COPS would follow those same longview content preparations steps as COPE. In addition, COPS should:

- Take into account the appropriate-ness of the content for each channel and audience

- Add in the editorial and messaging considerations unique to each

- Use the content only if it meets stated objectives and goals via those channels

These items should be present from the start. But, as I mentioned earlier, those considerations might not survive through the content workflow and the sometimes-dizzying personnel chain that accompanies it.

Selectivity is the key. We are not only talking about different devices for displaying our content. We are talking about different online platforms, too.

If the COPS theme wasn’t already playing in your head, LET ME HELP YOU OUT:

(Image adapted from “More Cops” photo by Flickr user Elmo H. Love (cc: by) )

1. Beret wearing. (College freshman, of course.)

2. Wearing bib-overalls in a non-agricultural setting. (High-school senior.)

3. “Pegging” my jeans. (Sixth grade.)

4. Head-to-toe camoflage in a non-military, non-outdoorsy setting. (Multiple occasions.)

5. Tuxedo with jeans and combat boots. (Junior prom.)

6. Hand-painting a 12″ peace sign on a mesh tank top. And wearing it. (Also sixth grade.)